America’s First Rock ‘n’ Roll Riot

And on July 7, 1956, America experienced its first “rock ‘n’ roll riot.” Ain’t that a shame.

Ain’t That a Shame : Thirty Years Ago, America Experienced Its First Rock ‘n’ Roll Riot.

The trouble started at the Palomar Gardens Ballroom in San Jose. The rumbling of a new era had begun to register on the historical seismograph little more than halfway through the 1950s; the sound of the approaching age was as strident as it was strange. It was called “rock ‘n’ roll.” Walter Cronkite described it as “a national juvenile mania.” And on July 7, 1956, America experienced its first “rock ‘n’ roll riot.”

The year began peacefully enough. In the spring of 1956, gangster Mickey Cohen became a born-again Christian, thanks to the ministrations of Billy Graham. On April 18, Grace Kelly of Philadelphia married Prince Ranier III of Monaco. On July 1, Joan Beckett was named Miss California after she gave a dramatic reading dealing with her dream “about the victory of faith over atheistic science.” Vice President Richard M. Nixon was visiting South Vietnam at the time. After only five minutes on the ground Nixon had learned to say, “Hello, how are you?” in Vietnamese.

But there was trouble, too, in the late spring of 1956. On June 2, Police Chief Al Huntsman of Santa Cruz broke up a rock ‘n’ roll concert in his city’s civic auditorium on the grounds that the teen-agers were dancing in “an obscene and highly suggestive manner.” In his moral outrage, the chief issued an edict banning rock ‘n’ roll music from Santa Cruz “forever.” People laughed at Huntsman’s severity–until July 8.

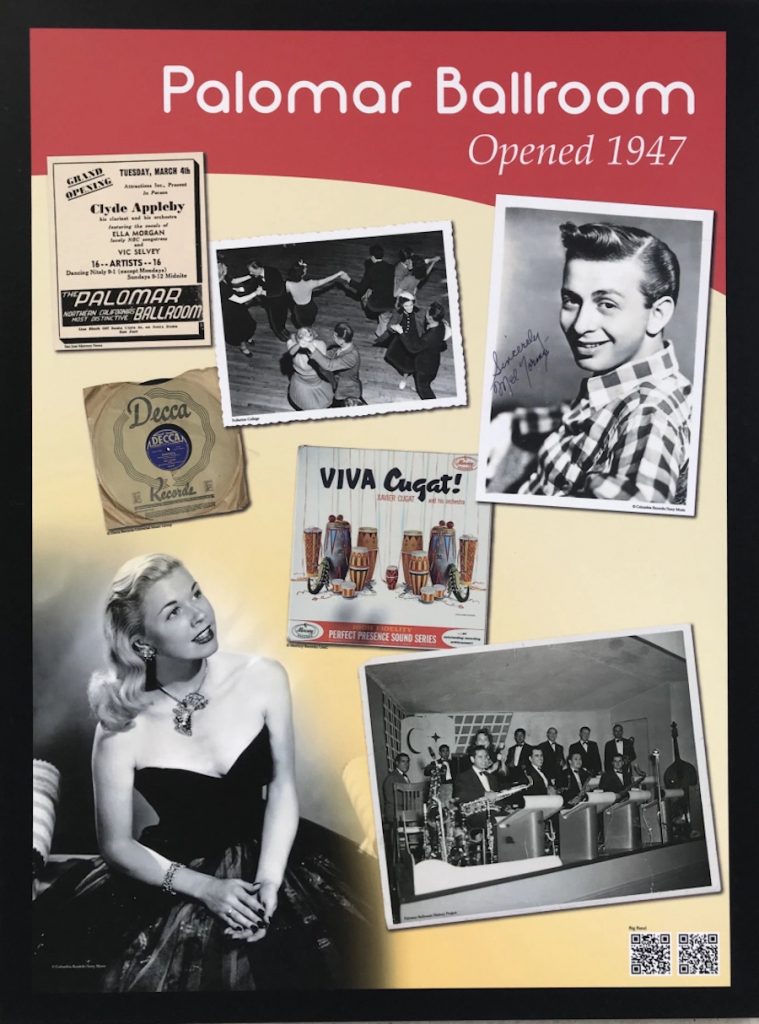

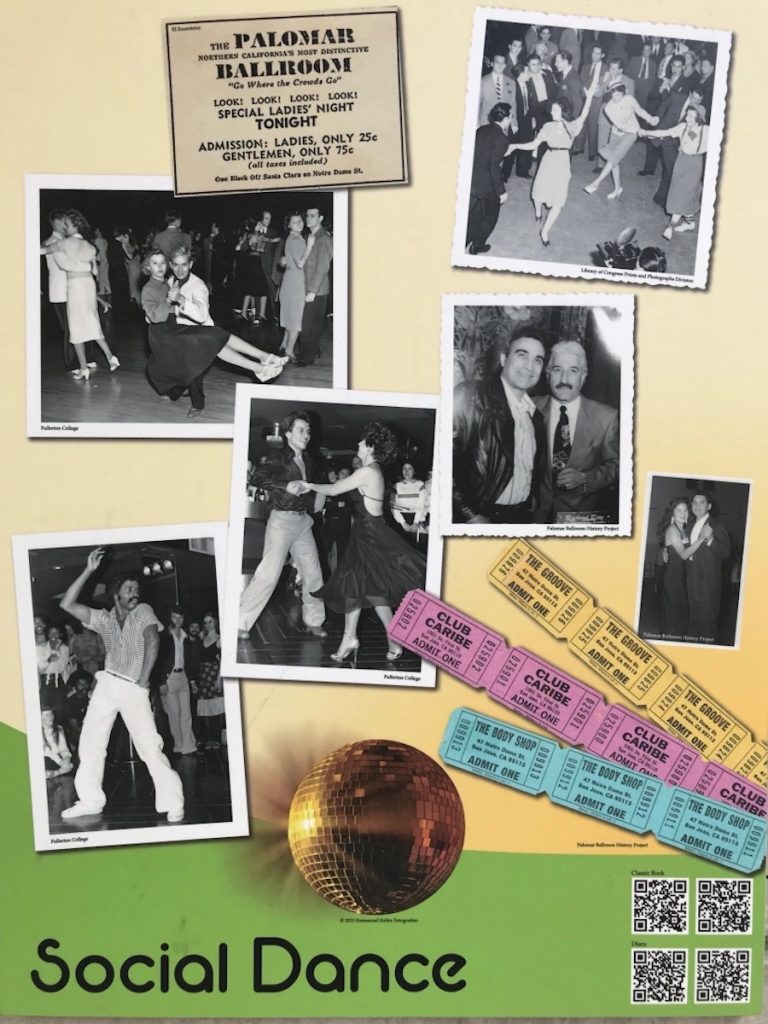

The owner of the Palomar Gardens Ballroom, Charles Silvia, had arranged for the first big rock ‘n’ roll show in San Jose to be held there the night of July 7. Ever since hearing a rock ‘n’ roll number by Bill Haley and His Comets a year earlier, Silvia had been trying to bring some of the new bands to San Jose. During the eight years since opening the Palomar Gardens, Silvia had hired some of the best big bands in the country. But by 1956 the crowds were getting smaller, and there seemed to be genuine enthusiasm only for rock ‘n’ roll.

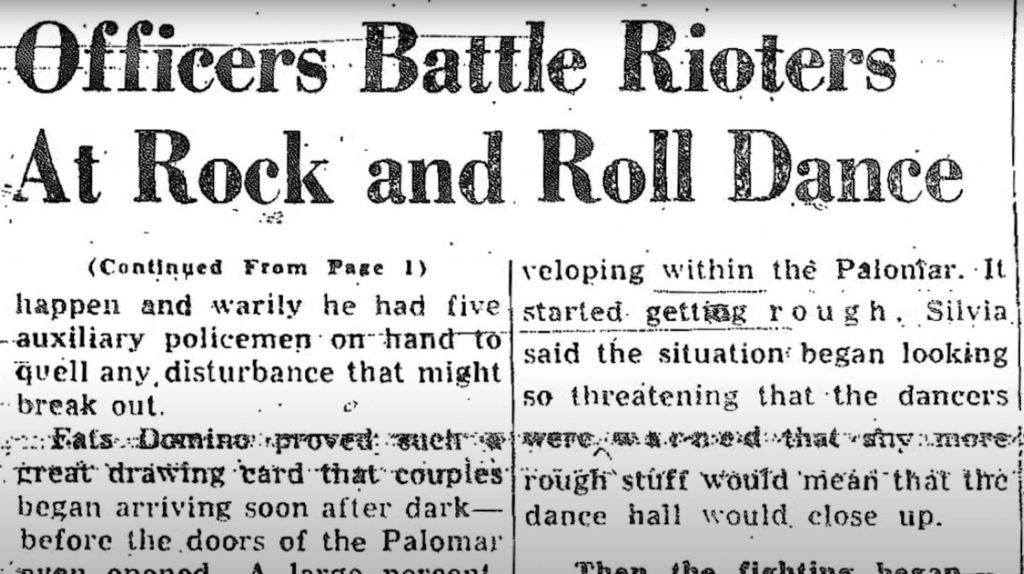

So when two Oakland promoters offered to bring Fats Domino and his band to the Palomar Gardens, Silvia quickly came to an agreement with them. Domino was one of the biggest rock ‘n’ roll attractions in the country. A year before he’d turned out the first of his big hits, “Ain’t That a Shame.” By July, 1956, Domino’s “I’m in Love Again” was No. 7 on the nation’s Top 10 charts. Silvia expected that the Palomar Gardens crowd for Fats Domino would be the largest ever.

Silvia had one absolute rule: When the doors to the Palomar Gardens swung open and the crowd surged in, he wanted the band to be on stage and ready to play. When people were willing to pay as much as $1.50 for a ticket, they wanted assurance, he believed, that there would be more than a token performance. Silvia wanted to be sure his customers got their money’s worth.

When Fats Domino hadn’t arrived by 8:30, Silvia began to worry. At 9, when the doors opened, and with the band still nowhere in sight, Silvia became very worried. The promoters assured him that there was nothing to worry about. But Silvia did worry.

But the multitude seemed to be in a good mood, and willing to wait. Business at the bar boomed. By 9:30, the hall was packed to capacity–and there was no band in sight. Empty beer bottles accumulated on the tables. A fight broke out in one corner of the dance floor; two police officers moved in and seized a young man who cursed them as he was escorted out a side door. His nose was bleeding and his shirt hung by a few threads. Within minutes, another fight broke out and then another.

Then Fats Domino arrived. It was 10:30. A loud cheer went up as the first members of the famous band climbed onto the stage with their instruments. Then Fats Domino plopped down at the piano and began to pound on the keys. To the heavy beat of “I’m in Love Again,” the crowd surged onto the dance floor. Silvia stopped worrying.

After almost an hour of nonstop music making, the band paused for an intermission. The 3,500 spectators and dancers in the hall returned to their tables, to the bar and to standing room around the edge of the dance floor.

As the hall quieted, someone near the back of the ballroom threw a beer bottle toward the stage. It crashed harmlessly onto the nearly deserted dance floor. Within a moment another bottle shattered on the floor and then a third. It seemed that a fight involving no more than five or six people was heating up. But others joined in. The overhead lights were hit and exploded, raining glass down onto the floor. Fist fights broke out. Within minutes chaos prevailed. Silvia couldn’t believe his eyes. A free-for-all was taking place in his precious dance hall. People were clawing, screaming, kicking, biting, punching and beating at each other. “Boys fought boys and even girls,” he remembered years later. “Girls were slugging and scratching at one another.”

Hundreds of frightened women poured into the restroom for sanctuary, then broke out the windows and jumped onto the sidewalk. Those nearest the exists were carried along as hundreds of terrified people made a rush for the doors. Then somebody threw firecrackers into the middle of the dance floor, and a series of flashes and explosions convinced hundreds that a gun battle was in progress.

Several blocks away, at the San Jose Civic Auditorium, the local police force was holding its annual ball. Just before Miss California was to be presented to the gathered dignitaries, Police Chief Ray Blackmore was told that a riot had broken out at the Palomar Gardens. He and his men hurried outside and jumped into six patrol cars lined up at the curb. With lights flashing and sirens screaming, they rushed into the breach.

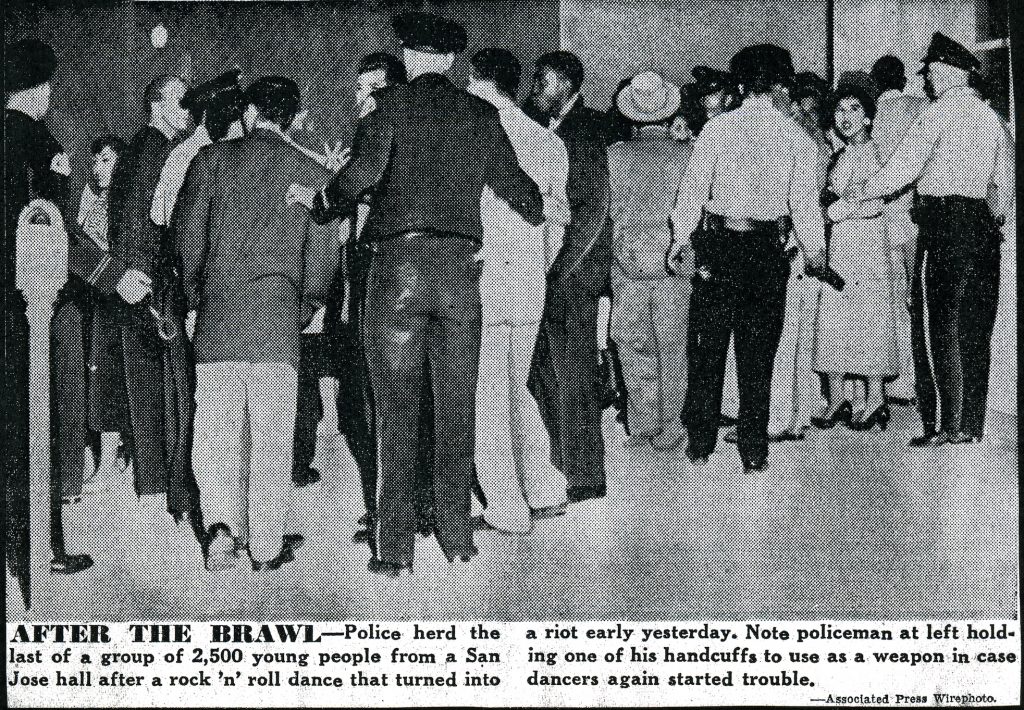

Police loudspeakers issued orders for the crowd to disperse; Blackmore ordered his men to arrest only the worst troublemakers and to let the others go. Finally, after a half hour, the beer-bottle supply ran low and the crowd scattered. Eleven people were carted off to jail.

In the next days, the story of the Palomar Gardens riot appeared in every major newspaper in the nation. The San Francisco Chronicle linked the music and the disorder by referring to the “rock ‘n’ roll riot” in San Jose. Other journalists adopted the Chronicle’s description; the Palomar Gardens riot became a rock ‘n’ roll riot.

The rock ‘n’ roll dance in Santa Cruz, followed by the San Jose riot, led many people to conclude that there was something inherently dangerous–even evil–in rock ‘n’ roll. A psychiatrist in Hartford, Conn., called it “a communicable disease.”

The San Jose City Council considered outlawing rock ‘n’ roll music in the city. However, Chief Blackmore said that it wasn’t the music but the beer that caused the trouble. “It was the fifth to the bottle rather than the eight to the bar” that inspired the riot, he said. Mayor Robert Doerr sided with the police chief, and the City Council settled for a ban on the sale of bottled beverages at concerts. In the future, all drinks would have to be dispensed in paper cups at concerts in San Jose.

Rock ‘n’ roll was given a second chance in San Jose. The next year, Silvia brought Fats Domino back to the Palomar Gardens. Beer was served in paper cups, and there was no riot.

But the debate on the alleged deleterious effects of rock ‘n’ roll continued. Politicians, parents, police and civic leaders wondered what to do about the popular music that seemed to drive teen-agers into a frenzy. They’re still wondering.

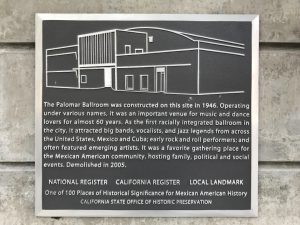

The First Integrated Dance Club in San Jose

The Palomar Ballroom, when it was opened in 1947, was a destination for many dancers and socialites in Santa Clara County. READ MORE

Next door to Hotel De Anza on Almaden Avenue.

Related Articles

Additional Did You Know's

Unraveling The History Of The First Grateful Dead Show.

The band’s members began their musical journey largely in the South Bay – leading epically to their first show under the “Grateful Dead” name at a house in downtown San Jose.

How San Jose Became Dead First — And Hosted The Band’s Debut Performance

December 4, 1965: The Grateful Dead’s first performance as the Grateful Dead occurred in a home in downtown San Jose now the site of San Jose’s City Hall.

Hal David Knew the Way to San Jose

The song earned Dionne Warwick her first Grammy and sold over 3.5 million copies.

Cupertino has ‘No Use for a Name’

A punk rock band from Cupertino formed in 1987 is highly praised in the Skate punk and Hardcore punk scenes. Their debut album, Incognito, was released in 1990. They had a Top 40 hit in the mid ’90s with “Soulmate.” In 1997, after the success of Making Friends, the band went on a worldwide tour…

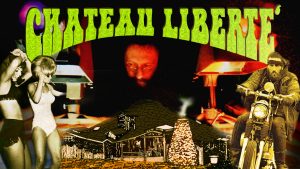

Los Gatos’ Chateau Liberte: Lights. Camera. Reaction.

The Chateau Liberte’ a feature documentary. The Chateau was a rustic mountain bar ran by Hells Angels where great rock bands played in the 60’s/70’s. It was also a hippie commune with its own self-sustained way of life.

Los Tigres Del Norte: the Beatles of Mexican music.

With half a dozen Grammys and sales in the tens of millions, able to pack arenas all over the country, Los Tigres del Norte—The Tigers of the North— is the most famous band mainstream America never heard of.

2020 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame: The Doobie Brothers

Since forming in 1969, The Doobie Brothers have sold more than 48 million albums, including three multi-Platinum albums, seven Platinum albums, and 14 Gold albums.

Larry Norman: the Elvis Presley of Christian Rock

San Josean Larry Norman is considered to be one of the pioneers of Christian rock music and released more than 100 albums.

Creedence Clearwater Revival: Go Spartans!

1967 – 1972: Formed by John Fogerty, Doug Clifford (born in Palo Alto), and Stu Cook in the late 1950s. Doug and Stu attended San Jose State, playing now under the name Golliwogs. In 1967 the band, now with Tom Fogerty, became Creedence Clearwater Revival.

Jefferson Airplane, South Bay Roots

Formed in August 1965 by Marty Balin, was populated mostly by South Bay musicians when he teamed up with Paul Kantner University of Santa Clara (1959-61) and San Jose State University (1961-63), Jorma Kaukonen (University of Santa Clara 1962) and singer Grace Slick resident of Palo Alto who joined the band in 1966.