Jorma’s Journey

March 8, 2008 By Mark Purdy, Santa Cara Magazine

His guitar playing helped define the psychedelic San Francisco Sound of ’60s rock. With nearly 30 albums and counting, his fretwork with Hot Tuna and on solo efforts has garnered him fans around the world. But once upon a time, he was playing the Nobili Hall cafeteria and handing out fliers that read “Jerry Kaukonen—Blues, Rags and Spirituals.”

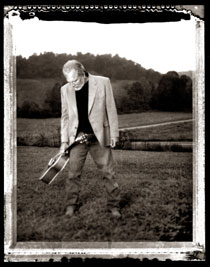

|

| Photo: Chris Kehoe |

In 1962, American pop music was a candy store of charmingly harmless (or some might say sweetly trivial) tunes. The Shirelles, Bobby Vinton, and the Four Seasons ruled the radio. But thanks to an incoming Santa Clara student who unpacked his guitar at Nobili Hall, the music world would soon become much more…groovy, man.

The student’s name was Jorma Kaukonen, although he was then known by his nickname of “Jerry.” Big things were ahead of him, though he could hardly have known that. Before he joined Jefferson Airplane, the poster band of psychedelic rock, Kaukonen spent 1962 through 1964 earning a sociology degree. He also played solo acoustic guitar gigs at local coffeehouses and impromptu “concerts” inside the Nobili cafeteria. In the process, Kaukonen formulated a key element of the Airplane’s signature ballroom sound—the loopy and soaring tangle of notes and chugging chords that went where music had never gone before. But as wild a journey as the Airplane offered, Kaukonen never lost his love for the blues or his affection for the time he spent at Santa Clara.

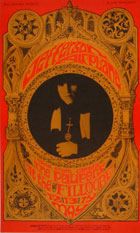

|

| May 1967: Kaukonen and the Airplane play the Fillmore © Bill Graham Archives, LLC |

“It was an interesting little school at that time,’’ Kaukonen said recently. “It was extremely conservative. There were a couple of us who were neo-beatniks. We weren’t real beatniks because we were going to school. But you know, we wore berets and stuff. We were the weirdos.’’

Kaukonen wound up on the Mission campus as a result of international fate and Jesuit prerequisites. His father worked in the U.S. Foreign Service and was posted to the Philippines, where Kaukonen attended the Ateneo de Manila, a university operated by the Society of Jesus. After the family moved back to Washington, D.C., he searched for a mainland school that would accept the Ateneo’s credits. Kaukonen was also fascinated by the hip Bay Area. All signs pointed to Santa Clara.

What Kaukonen could not have realized was that, moving into his dorm room, he would be diving into one of the 20th century’s most dynamic musical soups. He had learned to play finger-picking folk and blues riffs in high school, after being introduced to the songs and style of folk-blues legend Rev. Gary Davis, a lifelong influence on Kaukonen’s music. So when “Jerry” saw a campus flier advertising a neighborhood coffeehouse appearance by a bluegrass group with a female singer, he headed straight to the club and asked if he might sit in. The singer turned out to be Janis Joplin—who would eventually meld her bluesy delivery to the rock firmament by joining Big Brother & the Holding Company in 1966, growing another branch on the psychedelic sound tree.

Jamming in the Valley

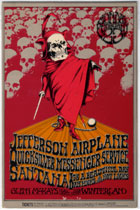

|

| With a little help from their friends: February 1970 at Winterland in San Francisco Artist: Randy Tuten; Postcard from the collection of Russell Morris Jr. |

Contrary to popular belief, the flowering of that famed Bay Area musical era began in the South Bay rather than San Francisco. The Grateful Dead emerged from Palo Alto and played its first show in downtown San Jose. Creedence Clearwater Revival began as a bar and frat house band called the Golliwogs while some members attended San Jose State. Kaukonen met another former Santa Clara student, Paul Kantner, at a surfer buddy’s house in Santa Cruz. The two worked the local coffeehouse circuit before moving north to join the electrified Airplane.

Most of these future rock stars, in various combinations, also played near the Mission campus at a youth center called the Watzit Club, which was launched by Santa Clara Jesuit Walter Schmidt. Kaukonen vividly recalls a guitar workshop in the Nobili dining hall when he worked out the initial complicated acoustic fretwork for “Embryonic Journey,” one of the Airplane’s most haunting songs, and a standout on the 1967 LP Surrealistic Pillow. A finger-picking tour de force, “Embryonic Journey” is so evocatively timeless that it was even used decades later to close out the final episode of the sitcom “Friends.”

Kaukonen’s favorite story, though, is of his first “headlining” gig—a weekend of appearances at the Offstage Club in downtown San Jose.

“At the end of Saturday night, I had made $75,’’ Kaukonen said. “I remember I was so excited that I invited everybody out for breakfast at the International House of Pancakes. That’s how I spent my first big paycheck.”

In Kaukonen’s memory, it was an idyllic existence. He woke up in his Dunne Hall dorm room, attended classes in the morning, then after lunch rode his motor scooter to the Benner Music Store on West San Carlos St. where he taught guitar—often to other Santa Clara students. One of them, Nick Talesfore, who attended Santa Clara in the early 1960s, has never forgotten the time he spent with Kaukonen.

“For my 21st birthday, my parents gave me guitar lessons at Benner’s,’’ Talesfore said. “Jerry and I would meet twice a week in a dingy basement practice room. I would give Jerry the $10 for the week’s two lessons and then we would go over the previous week’s assignment with him brutally critiquing me. He would then record our next lesson while I sat there amazed at his timing and fingering. I was mesmerized. I still have those tapes.”

At night, after Kaukonen wrapped up his teaching duties, he would hit coffeehouse jam sessions across the valley with the likes of Grateful Dead founding members Jerry Garcia and Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, as well as David Crosby, Kantner, and Joplin.

“For some reason, there was some synchronicity,’’ Kaukonen said. “It was really a sociable music scene. Even though there were egos, everybody was supportive. It was sort of like an extension of a house party.”

The party, as you might expect, didn’t always leave enough time for his studies. Kaukonen admits they weren’t his top priority. But he met his graduation requirements, and his work was impressive enough that his senior thesis advisor, Gerald McDonald, told him to forget the silly music stuff and think about graduate school. Kaukonen politely declined the suggestion. Within months, he would catch the break that affirmed his gut instinct.

A Jet Aged Sound!

During Kaukonen’s senior year at Santa Clara, the Folk Theatre nightclub in downtown San Jose closed. “Paul Kantner talked me into going up to San Francisco, where I met Marty Balin,” Kaukonen said. “They asked me if I was interested in trying out for their new band. At the time, I was what you might call an ethnic purist about acoustic folk and bluegrass music. I had just graduated and wasn’t thinking about making money or a career or anything.”

In fact, Kaukonen was thinking about heading off to Europe to make a go of it as a blues musician. “But rock and roll was very seductive,” he said. “So I agreed. Ken Kesey, who was living in the mountains above Stanford, came by the audition at the Matrix nightclub and he had this electronic thing that created a guitar echo so you could play a solo with yourself. I plugged my guitar into it and…was seduced by the technology, I guess.”

Kaukonen also brought something else to his new band—its name. A musician friend in Berkeley, Steve Talbot, had nicknamed Jorma “Blind Thomas Jefferson Airplane” as a fun-loving tribute to blues guitarist Blind Lemon Jefferson. As the new band batted around ideas for what to call itself, Jefferson Airplane was kicked onto the table. And it stuck.

Jefferson Airplane played its first San Francisco gig, at the Matrix in August ’65. Two years later, Kaukonen and the Airplane were the house band for the Summer of Love and jetting around the country, playing to packed arenas as Kaukonen created some of rock’s most enduring and profound riffs.

Yet even before the group disbanded in 1972, Kaukonen had shifted gears and formed Hot Tuna with his friend, Airplane bass player Jack Casady. Returning to his pedigree in blues and folk music, Kaukonen built Hot Tuna from a side project into a popular attraction that easily stood on its own merits. The band’s repertoire educated many young rock fans in the beauty of American roots music. He also worked as a solo artist, showing off his rugged, plain-spoken vocal style that was rarely featured with the Airplane. In 1996, he and the band were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

For all of his musical success, Kaukonen remains fiercely proud of his sociology degree. It was mentioned right there in the liner notes for the band’s first album, Jefferson Airplane Takes Off, released in August 1966. More than 40 years later, Kaukonen says: “The diploma is on my wall at home.…Looking back on things, I really enjoyed what I got out of Jesuit teaching. Santa Clara gave me the opportunity to learn what would define my life—my sensibilities about humanity and my guitar playing. And there was an audience to play to, even if it was a minuscule one. I owe the school a debt of gratitude. I was a crummy student, but I got it done.”

These days, at age 67, Kaukonen still tours several months a year. Bay Area fans flocked to hear him last fall at the Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Festival in Golden Gate Park and, later, at the Fillmore Auditorium. During Kaukonen’s festival set, the Blue Angels made an overhead cameo. Unfazed by the deafening roar of the Navy F/A-18s, Kaukonen asked the crowd, “What key do you think those planes are in?”

That playfulness, and a comfortable-old-pair-of-jeans return to Kaukonen’s roots, is what you’ll find on his latest album, Stars in My Crown, released last spring. In the liner notes he writes: “I find myself living a simple life with my music.” The collection of songs is reflective and traces the threads of a tuneful life, weaving together originals and compositions penned by Lightning Hopkins, Johnny Cash, and —see how it comes full circle?—a couple by the Rev. Gary Davis. There’s an unabashed sweetness to Stars, a gentle wisdom won through years. They could be seen as songs of faith that ask the question—which Kaukonen does, out of joy rather than self-satisfaction: “Who would have thought that life would be this good?”

After one San Francisco show a few years ago, Kaukonen was visited by former guitar pupil Talesfore.

“We reminisced about the lessons at Benner’s and the Epiphone Texan acoustic guitar he’d sold me,’’ Talesfore said. “He asked if I still had it and when I told him I did, he told me what a great guitar it was and that I should never sell it—which I wouldn’t. I was impressed at how much he hadn’t changed over the years despite all his talent and fame.’’

Kaukonen is, in fact, still in the business of giving guitar lessons—but in a much more bucolic spot than Benner’s basement. He and wife Vanessa operate the Fur Peace Ranch near their Ohio home. Each summer, Kaukonen serves as lead instructor at the ranch’s series of residential camps where, as an esteemed tribal elder, he passes on his knowledge to both young and old musicians. It’s a long way from his days as Nobili Hall’s neo-beatnik weirdo. He admits that he never attended a football or basketball game while on campus, but when asked if he has any message for his fellow Santa Clara alumni, he responds quickly.

“Yes,” Kaukonen says. “Go Broncos.”

Mark Purdy is a sports columnist for the San Jose Mercury News and mercurynews.com. He is also a board member of San Jose Rocks, a non-profit organization that celebrates Silicon Valley’s historic role in rock music.

What Say You Mark?

“When I moved to San Jose in 1984, I was fascinated to learn that it was the often-uncredited spawning ground for so much great rock music of the 60’s and 70’s. It turns out that while San Francisco was busy admiring itself in the mirror, San Jose was doing a lot of awesome grunt work to construct the framework of that era’s Bay Area sound. For me, researching and documenting the origins of the South Bay bands and the music they created has been a fun archeological expedition. If San Francisco is considered the King Tut’s tomb of Bay Area rock history, then the South Bay and San Jose are the tomb’s antechambers full of glorious untold treasure. San Jose Rocks exists to explore and honor that treasure.”

Mark Purdy, March 5, 2021

About Mark Purdy

Mark Purdy spent 43 years as a sports reporter and columnist for the San Jose Mercury News, Los Angeles Times, Cincinnati Enquirer and Chicago Tribune. But in addition to covering 14 Olympic Games and 34 Super Bowls, he also wrote stories or news columns about politics, music and food. He had lunch with Muhammad Ali, played golf with Neil Armstrong and discussed baseball with Alice Cooper. Since his 2017 retirement from the Mercury News, he has taught at San Jose State and Santa Clara University while also writing freelance magazine articles and video scripts. On multiple occasions during his career, Purdy was named one of America’s Top 10 sports columnists by the Associated Press Sports Editors and was cited by the Wall Street Journal for writing one of America’s Top 10 sports columns. In 2011, the California Newspaper Publishers Association honored him for writing the state’s best newspaper column in any category. He was a member of the Mercury News staff that received a Pulitzer Prize for its coverage of the 1989 Loma Prieta “World Series” earthquake that struck just before Game Three at Candlestick Park. Purdy is a native of Celina, Ohio, and a graduate of Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism.